Tupelo Honey

Van Morrison

Is It Real

Education (Center)

Education (Center)

Louis Comfort Tiffany

http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tiffany_Education_(center).JPG

There was an article in the Guardian a few weeks ago about hoaxes, “The greatest literary hoax ever?”. The article talks about how the writer William Boyd got together with a number of influential friends to invent and promote an artist who never existed. Before they were done, they were exhibiting this artist’s paintings and getting well known, and not so well known people, to talk about how they knew and admired this artist. Before he could bring the hoax to its planned conclusion a co-conspirator let the secret slip out. It makes for an interesting story and illustrates the gullibility of people. The song is about placing values on things, and recognizing the best and being willing to make certain investments (all the tea in China, for example) to demonstrate this value.

The picture is of one of three stained-glass panels done by Louis Comfort Tiffany celebrating education. If we are well educated we are perhaps less likely to be caught in a fabrication and more able to access the accurate and true values of things. But maybe not. Boyd’s crowd of art admirers included well educated people who ought to have known better. Perhaps this was what the hoax was playing off of. If these people expected to be taken seriously as knowledgeable appreciators of art they must not let it be supposed there are influential artists of whom they were unaware. Perhaps the first thing the truly knowledgeable learn is that they do not know everything and that there is nothing wrong with not knowing everything.

Of course the story that Boyd invented was a good story and perhaps what truly lay at the heart of the deception was a human desire to be a part of a truly good story, even if that means inventing a personal history that is different from one’s true history. Or maybe the story was so good it suggested artists from these people’s past whose names they had forgotten but whose work they held onto. Maybe the works they shared were done by a corps of unknown artists that met early and tragic ends. Maybe the invented story was the story of many unknown and unappreciated artists that gave into despair. In the stained glass panel celebrating education at the top of the page the two disciplines represented are “science” and “religion,” two disciplines that often interpret the truths they encounter by different lights and maybe both offer a truth that resonates even if at times they conflict. Each often accuses the other of perpetrating hoaxes and each answers these accusations rationally according to their separate understandings. As one dubious judge once remarked “What is truth?” Perhaps all truth begins with faith in something and it is on that something that all that follows rests.

Illustrations from Old French Fairy Tales

Illustrations from Old French Fairy Tales

Virginia Sterrett

http://www.subtlebody-images.com/virginia.sterrett/vs.fairy.tales.html

As an English teacher I think stories teach basic truths about the world humans inhabit. These stories are fiction and it would seem by definition are not true. It is something of a paradox, perhaps, that something that is fabricated, like a story, can illuminate so much and give such insight. The illustration above was done to illustrate a fairy tale. Fairy tales introduced most of us to the world as it is, a world of “evil stepmothers” that cannot be trusted and “fairy godmothers” that can. Yet there is in this something of a life lesson, many that should be trusted cannot be, and many that should be doubted can be trusted. Much of life revolves around sorting out these kinds of problems.

There was an article last week, “Mind your language,” also in the Guardian about language and how we use it. The specific word in question was the word “skeptic” and what that word literally means. According to the article a true skeptic is a seeker after truth and questions everything in order to discover what is true. Yet the word is being applied to those that question nothing their own ideology teaches and doubt everything that challenges that ideology, often without doing very much to sort out which is in fact true. In other words the very opposite of a skeptic in that they accept one body of knowledge without question and challenge any contradictory body of knowledge without examination.

Corner House

Corner House

István Orosz

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Cornerhousey.jpg

The illustrations above and below are interesting in this regard in the way they play with perspective. The one above is of a corner of a house. But is it an outer corner or an inner corner, does it open on a courtyard or a sidewalk. As I look at it the perspective changes, one minute it is turning a corner and the next it is at the back of a corner, one minute one window is invisible to the other, the next it is facing the other. Which is true? Of course, in this picture anyway, they are both true, it all depends on how we look. Is this a work of art or geometric gamesmanship? It is hard to say, but it is kind of fun to look at.

The picture below is of two roads, or bridges really, that cross a body of water but at some point beyond where the two cross each disappears into its reflection in the water. The pictures are Escher-esque in the way they play with perspective, but they offer a kind of pleasure in the way they play with how the eye focuses and sees. Stories often teach us that life is about maintaining our perspective on things, about seeing things correctly, even though life often presents itself in a confusing and incomprehensible manner. Is the nice lady in the gingerbread house inviting us for dinner or “having” us for dinner? The answer to this question, whether it is literal or metaphoric, often determines whether the day’s events have a happy or unhappy conclusion and as with the pictures, appearances can be deceiving.

Crossroads

Crossroads

István Orosz

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Keresztut.jpg

A good story often challenges our way of viewing the world and in so doing reminds us we have to be careful in our judgments and not lean to heavily on our own understanding. It is not always easy to tell where the line falls between being gullible and being open minded, between being generous in our treatment of others and being foolish. Stories do not always help us resolve these problems but good stories make us aware of these problems and the need to resolve them while being true to our character and values. The most dangerous people in the world are those that understand us and what we believe and know how to exploit those beliefs and in the process exploit us. Stories cannot solve these problems perhaps, each situation must be addressed by its own merits, but they can make us wary and wise in our approach to circumstances and events.

The Dot and the Line

Metro Goldwyn Mayer

I like this little story because it addresses the romantic and the realist in all of us. Both the dot and the line are vulnerable to their romantic inclinations and these inclinations lead them to make unwise choices. Fortunately for them, and unfortunately for the squiggle perhaps, the story has a happy ending and both the dot and the line are able to experience romance realistically, though I am not sure that means of their deliverance is itself realistic. But we understand when the story ends that dot and the line are “right” for each other.

Is this story true to life, do things often resolve themselves so neatly? Probably not. The value of the story lies in its pointing out the blindness that romance can bring and hopefully put us on our guard against it. But than other stories, Great Expectations, perhaps, suggest that even when we realize that our emotions and romantic attractions are leading us astray we are powerless when it comes to resisting them. We often find out the hard way, through pain and disappointment, that our affections are not always reciprocated and that those we have never harmed will seek to harm us.

Screenshot from the film Metropolis (1927)

Screenshot from the film Metropolis (1927)

Karl Freund, Günther Rittau, Walter Ruttmann (cinematograpers)

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Metropolis-new-tower-of-babel.png

Anyone who knows Breughel’s painting of The Tower of Babel will recognize it in this landscape from the film Metropolis. This knowledge should shape the way we view this cinematic landscape and the story this film is going to tell before the film begins to tell it. The story of Babel ends in tragedy and it is about human arrogance and presumption. The film addresses another kind of human presumption and arrogance, one that has more to do with exploitation of others than of usurping the powers of God, though there is a bit of this as well. But allusion is one way stories tell stories without actually telling the story, they prepare us for what is coming and help create a frame of mind in the reader (or in this case the viewer) that attunes itself to what appears to be coming. We see this picture and knowing its origins we know that what follows will be tragic, or with a different set of cultural signals, comic. The film The Music Box with Laurel and Hardy is, at least in part, a comic retelling of the Myth of Sisyphus. We catch on to how the film plays with the myth early on but because it is a Laurel and Hardy film, we expect a comic and not tragic retelling of the tale.

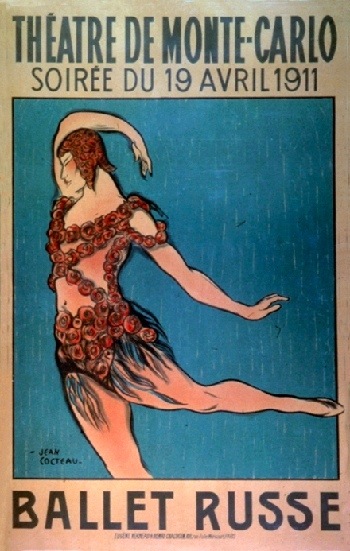

Poster for the 1911 Ballet Russe season showing Nijinsky in costume for "Le Spectre de la Rose", Paris.

Poster for the 1911 Ballet Russe season showing Nijinsky in costume for "Le Spectre de la Rose", Paris.

Jean Cocteau

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Nijinsky_-_Poster.jpg

Nijinsky was an influential Russian dancer and the ballet Russe an influential dance company. The ballet is The Spirit of the Rose. I know nothing about the ballet, but the name is suggestive. “A rose by any other name” and The Name of the Rose are just a few of the literary associations of the rose. It represents beauty and a kind of excellence. Another odd bit of serendipity in this poster is the artist that painted it, Jean Cocteau. He would go on to become a 20th century pioneer of the French cinema. He told powerful film stories. One of his best known films was Beauty and the Beast, not the Disney version by any means, but still a forceful retelling of the original fairy tale, which kind of brings us back to where we started, or near to it. Fairy tales do not just prepare children for the cruel world they may face as adults, but they often remind adults of the darker side of the world they have grown into.

Cocteau’s film was not made for children, though its characters, themes, and settings come from a very well known and beloved children’s story. The story he tells is very dark, but at the same time childlike. There was also this week an obituary for the last Yiddish poet, Abraham Sutzkever. One thing he said that is true of stories and storytellers was "If you carry your childhood with you, you never age." As children the stories we read help us age wisely, as adults these same stories help us to age gracefully, preserving in us what is best of youth and maturity.

No comments:

Post a Comment